5 Success Stories that Prove Economic Crises Aren’t Always Bad for Business

Economic downturns are not always all bad news for businesses. Here’s why:

- Downtrodden economies can lead to great innovation. Existing companies must find new ways to survive and thrive, launching products that might not have fit in better moments and getting creative about stretching funds.

- People out of work can now invent their own jobs; they’re known as survivalist entrepreneurs.

- Finally, recessions create new and different customer demands, like for cheap entertainment instead of expensive vacations, so businesses in suddenly popular industries can flourish.

Here are five companies and products you might not know were born out of economic recessions. Not all are still small, though most started that way!

1. FedEx

When OPEC quadrupled its oil prices in the early 1970s, the U.S. hit a period of recession, stagflation, and high unemployment. FedEx, founded in 1971, started shipping packages in ’73, just as the oil embargo began. The next two years almost destroyed the company: Fred Smith, the founder, ran through most of the $84 million dollars he’d raised, in spite of the fact that he was accomplishing the company’s mission, to deliver documents overnight. But doing so meant spending bundles on rising fuel costs. The founder’s commitment to his mission kept the company afloat, as did an innovative ad campaign that convinced customers his service was a necessity: “FedEx—when it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight.” His efforts paid off: by 1980, profits hit $38.7 million.

2. Kraft Miracle Whip

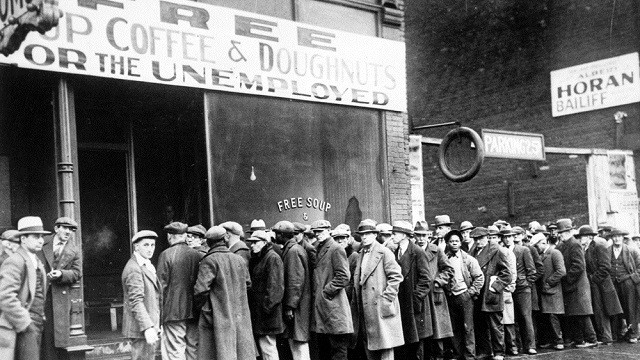

Once Richard Hellman introduced the gooey spread at his deli in the early 1900s, Americans became mayonnaise lovers. But thirty years later, during the Great Depression, people could no longer afford the condiment, which is made out of pricey ingredients: eggs, oil, and vinegar. Kraft, whose mayo sales were slipping, devised new emulsifying technology in order to create a mayo alternative. The machine made it possible to whip cheaper ingredients, from high fructose corn syrup to water, into oil, creating Miracle Whip, the fluffy, creamy, sort of mayo-like spread.

3. iPod

Steve Jobs’ Apple brought the first-generation iPod to market in October 2001, in the wake of the dot-com bust of 2000. Though the device’s $399 price tag was hardly recession-friendly, 600,000 people bought one by the end of 2002. That number rose to 2 million a year later, according to Cult of Mac. The iPod wasn’t created because of the recession’s hardships— it was part of Steve Jobs’s strategy earlier on—but the huge sales were evidence of consumers looking for relatively cheap enjoyment during that time: it’s less expensive than a stereo, going to concerts, or buying a TV. For Apple, the success meant the company could rely on a cashc ow product line as the country’s economy recovered.

4. King Kullen

A Kroger employee named Michael Cullen had the idea to start the modern supermarket—a place with tons of goods, self-service shopping, and discounted prices—but his boss at Kroger didn’t bite. So, he left his position to start King Kullen. The first store opened in Queens in August 1930, and success came quickly; by 1932, there were eight locations, due to the low prices that matched Depression-era budgets. Today, there are 36 supermarkets on Long Island, and Cullen holds the honor of having founded the first iteration of the modern supermarket (Smithsonian).

5. General Motors

Just after the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. economy underwent The Panic of 1907. The country didn’t have a central bank yet, and excessive lending eventually led to a run on financial institutions. The panic lasted just a month, though it took two years for the economy to recover and businesses to regain access to loans. All that chaos didn’t stop GM founder William Durant from innovating. He’d been making horse-drawn carriages before the panic and turned to automobiles in 1908. Though he was hardly the first entrepreneur with the idea, he was the first to accelerate his Flint, MI-based engine company into an auto manufacturer. Then, as the economy recovered, he was able to turn the business into a clearinghouse, buying other carmakers, like Oldsmobile, Cadillac, and Pontiac, and running manufacturing, sales, and R&D at scale.